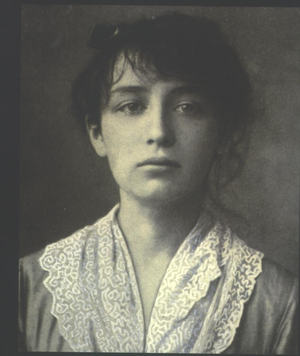

It was with neither teacher nor model that Camille Claudel started working clay —(lost) figures of illustrious characters, a sketch of a David and Goliath made when she was 12 or 13. In 1881, her family moved to Paris. The following year, the artist produced the bust of La Vieille Hélène, marking the end of her period of apprenticeship. She was then 17, taking classes at the Colarossi Academy, and moving into her first studio. Alfred Boucher, a sculptor from Nogent-sur-Seine, kept an eye on how her works were progressing, but when he decided to go to Italy, he asked Auguste Rodin to take his place. The sculptress attended Rodin’s studio —that was the time when La Porte de l’Enfer [The Gates of Hell was being created] (1880-circa 1890)— and swiftly became his associate, confidante, and alter ego. Their works influenced each other and merged. In the spring of 1886, their relations grew very tense, and she fled to England. On her return, Rodin drew up and signed a paper in which he undertook to be her patron, and marry her. They worked just a few feet from one another. La Valse [The Waltz] (1889-1905), which sensually expresses the intoxication of love, with bodies swept away until they lose their balance, embarked Claudel on the road to fame. She tried to obtain a State commission for its production in marble, but had to alter the composition and clothe its dancers; her new version, produced in 1892, was eventually championed by the inspector of fine arts, Armand Dayot; the order was never actually signed, but the work was cast in bronze and exhibited in 1893, much admired as a masterpiece in harmony with the Symbolist spirit and Art Nouveau. But there was a famous Valse, and a sad Valse; while it brought her recognition, her life was suddenly shattered: 1893 was in fact the year when she broke up with Rodin. She then created Clotho, Fate entwined amid the snakes of her hair, an old lady with a broken body and a morbid grin. Then began the lengthy genesis of her first State commission: L’Âge mûr (1894-1900), a figure of a man split between an elderly woman holding him up, and a young woman, imploring him—this latter figure, re-used on its own, would become L’Implorante (1893-1897). The sculpture spoke for itself: Rodin had given up any idea of leaving Rose Beuret, his partner of thirty years, and went to live with her in Bellevue. Over and above the pain in which it is steeped, the work reveals the sculptress’s artistic independence. As the outcome of so much work and isolation, and the evocation of so much suffering, L’Age mûr marked the artist’s entry into a time of despair. It was nevertheless in that period that she came up with her most original works, the “croquis d’après nature” sketches from nature (1893-1905), precious, small-format works, combining bronze, stone and marble onyx. The first of them were snapshots of life, but the ensuing works focused on the chasms of thought and solitude. In 1899, Claudel set up home at No. 19, quai Bourbon; there now took root in her, little by little, a sense of persecution, and the fear that her work would be plundered— by Rodin, from whom it had been so hard for her to separate. Exhaustion overtook her; and her inspiration dimmed, too. In 1905, when Eugène Blot held an exhibition of her work in his gallery, she proceeded to systematically destroy her sculptures. Her brother, Paul Claudel, demanded that she be “voluntarily committed”. On 10 March 1913, Claudel was taken to the lunatic asylum of Ville-Évrard, and then transferred to Montdevergues on 12 February 1915, which is where she expired. During her thirty-year confinement, she received no news, and no letters: this was the express instruction that her mother was forever renewing with the asylum’s administration; and when the doctors suggested a permit to leave the place, or an establishment closer to Paris, such ideas were also firmly opposed. The sculptress wrote endlessly, clamouring for freedom, whatever kind of freedom that might be: “just a barn at Villeneuve” and “realizing that dream: of being at home”.

Anne LEMONNIER

See this illustrated text on the website of the Archives of Women Artists, Research and Exhibitions